Great landscape photos generally fall into two categories, photos created with patience and planning, and photos that are happenstance. I am a firm believer in both. While pushing to create amazing landscape photos, there will always be images that are only realized once you are in place.

For more examples of my Vermont landscape photography, other nature photos, and many more, visit my website, www.DavidSeaver.com

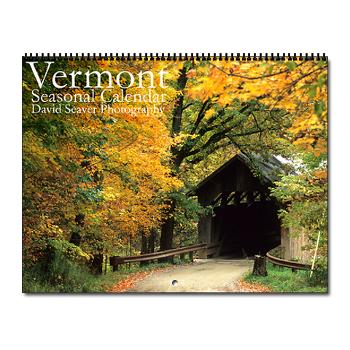

Vermont's fall foliage. Nikon D2X, 17-35mm, Circular Polarizing filter

Living in Vermont, I consider myself extremely lucky with the abundance of beautiful landscape opportunities within a short drive (or walk from the house). Vermont’s fall foliage is legendary, and I would argue one of the world’s most amazing seasonal occurrences. The range of colors, the mix of light, the varying weather, and the blending of seasons make autumn photography an easy draw for thousands of photographers and tourists each year. While fall foliage may be one of Vermont’s best known attributes, landscape photography is an ongoing, year round, all weather pursuit. I’ve spent countless frosty pre-dawn mornings racing to find the perfect frozen leaf in a field of glistening grass, and trudged through hip deep snow to get the right angle on a deep winter scene. Each season presents it’s own highlights and peculiarities and this is where gaining as much knowledge of your surroundings, weather, sunrise/sunset times, moon cycles, and local customs and laws can take an interesting scene to the next level. I am constantly returning to the same places in different seasons, looking for that special touch of light, or a light fog to give it that something extra.

Sunflowers in Vermont. Nikon F100, Fuji Velia 50, 70-200mm

Although I wouldn’t consider myself a morning person and have tens of thousands of sunset and late day shots, there’s something magical about the early morning, before and right after sunrise. Unique things happen in the morning. Frost only lasts until the sun hits it, giving you a maddeningly brief amount of time to shoot those crystals. Fog, while not unique to the morning can sometimes be most reliably predicted in the morning (I’m speaking only of Vermont here, not of coastal areas where fog can come at anytime). In winter, fresh snow has a certain twinkle that seems to diminish as the day progresses. Skies are also sometimes clearer in the early morning as the clouds haven’t had a chance to form throughout the day. The earlier you get out there, the less you have to deal with traffic and human interruptions. Driving around and stopping on country roads can be hazardous, especially with sleepy drivers on their way to work, but generally most people wave and look longingly at the scene that you the photographer is experiencing first hand.

Cows at sunset, Vermont. Nikon F100, Fuji Velvia 50, 24mm

There are endless ways to shoot landscapes, from the macro to the mountains. My approach is to head to a place that I think will give me the best opportunity to get a good wide shot, and fill in with details, tight telephoto shots, and all the other combinations once I’m there. My forethought always involves the sunrise times, combined with where the light will be entering the scene, how the shadows play with the highlights and if there are any unique things happening. Putting yourself in the right spot at the right time will help you get a good shot, but you still have to compose a striking and engaging image to capture a viewers attention.

A fence in winter, Vermont. Nikon F100, Fuji Velvia 50, 70-200mm

Composing great landscape photographs is a game of what to keep and what to cut. Are you looking for a clean scene, or one with many parts. A good way to approach landscape photography is to start identifying your foreground, middle ground and background. Yes, those mountains are beautiful, but by including something, a flower or grass, in the foreground can give the photo depth and ground it with a sense of scale. Think of Bob Ross’s famous painting shows. He always worked with fore, middle, and background elements, each adding their own weight to the image.

Red maple leaf in Vermont. Nikon D2X, 50mm

As I’ve discussed in earlier posts, composing great photos isn’t about putting something in the center of the frame. Push a tree to the side, let the river trail off into the distance, give the sky lots of room (or don’t). Move the camera around. Lay on the ground, climb a tree. Try to get that new perspective that no one has thought of yet.

Vermont country road with fall foliage. Nikon D2X, 17-35mm

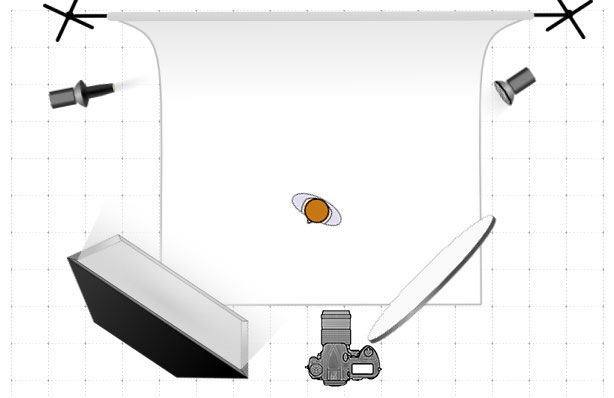

While the classic image of landscape photographers is one with a large format camera and a heavy tripod resting on their shoulder, newer digital cameras allow more ability to handhold photos with a great depth of field. That said, shooting on a tripod at your slowest ISO and high f-stops is always a good idea if image quality is what you’re looking for. Shooting on a tripod also forces you to slow down and pay attention to composing an engaging a great photo. The detail of a medium or large format camera is perfect for landscape photos, but the cost and technical skill required is beyond what most people want to get into.

Snow falling at night. Nikon D2X, 17-35mm, 2-3 second exposure

Post production can be an integral part of great landscape photos. The difference between a flat photo and one with dynamic tones and shades of light can come down to what happens after the fact. The best example of post production perfection was Ansel Adams, a master printer who would coax a feeling out of his photos while in the darkroom. If you ever get a chance to see a real Ansel Adams print up close, do it, the look so much more impressive than the copies and posters that fill our world. While some photographs come out of the camera looking the way they should, many don’t. I’m not opposed to cropping or burning and dodging, but adding or subtracting things from a scene changes it from a landscape photo to a digital creation. I would consider myself a purist, shooting what the world presents. I only occasionally use filters and limit them to polarizers and neutral density filters. I think the colored filters can give photos a very fake look. They stick out like a sore thumb in a bunch of well crafted images. The same can be said for HDR photos, which tend to look gimmicky after seeing more than one.

Looking up at the color of fall, Vermont. Nikon D2X, 7mm fisheye

So keep shooting. Keep going back to places you’ve shot before. Keep seeking out new places. Landscape photography is ongoing and essential for preserving our nature and capturing this time and place.